I tried to be an anarchist for a little while, not very hard, admittedly. Only as long as it was interesting, aping the wild kids with their neo-tribal get-ups and crazy train-hopping tales. I knew that, whatever my intentions, it wouldn't work. I was not, am not a true believer. Sooner or later I was going to run like Gulliver from the Brobdingnagians (or whatever they were called). The reason for this is that, in my heart of hearts, I did not care that a large number of English children died of starvation, black lung, and/or industrial machine malfunction in order to produce the decadence that made Oscar Wilde's flowered necktie possible. I preferred Oscar Wilde, an unnecessary dandy and wit-about-town, to a number of innocent, common, tortured children. Therefore I could not be an anarchist. Nor can I be anything at all useful in the world. In fact, I did the only thing my talents and this perversion allowed, which was to read a lot of literature and write useless stories.

I confess that I do not believe in equality, a requisite thing for any reformer. Philsophically, yes. Ideally, without a doubt. Each soul is glorious, irreplicable, and so beyond value that the word "perfect" is an insult. But equality is an artificial attribute. Why throw away children? Because I can't. Because they aren't my children. Because I have no say in it. God has already killed them, and no amount of violent, egalitarian rearrangement (however much I love to "smash shit," however earnestly God smashed his own shit on the cross) will bring even one back. (Interestingly, I just remembered that this is what Ivan Karamazov said... and Alyosha's answer, his great mystery and first commandment given to him by the dying elder, was, "You ARE responsible for every man. Every man's sin is your own." Hardly Christian...)

In "A Tomb for Boris Davidovich," Boris the aging revolutionary par excellence fights the interrogator to write his own story, himself as Revolutionary. This is his tomb. Oh it is a beautiful story. Does he get his tomb? Every word is a stone, set, then destroyed, then set again with all the agony and devotion of an animal struggling against death. This is all that matters. What revolution? Build your monument. Wear your flowered necktie. Love the children. God loves them and the capitalists. God loves the brick and the window. God will kill the children. God will kill the anarchists. God killed Oscar Wilde.

P.S. I understand that it is unfashionable to use the word "God." I should have substituted "life," "Nature," "the universe," or some such other abstraction. To me, it will always be God. So what. If you believe in the death of the author, you may read in whatever noun you prefer. Cabbage, for all I care.

Wednesday, September 30, 2009

To the Wanderers:

I feel you.

It's the cusp of the month. When I was in high school, this meant nothing. When I was in college, it meant that I would sign a check. When I was at Betsy, it meant that it was time to collect the always-too-little I'd gotten from various un-jobs and beg for the remainder from charitable souls. Now I'm just hoping I'll have someone to write a check to. I'm done with this house. Can't live here anymore. I put in my month's notice... looked for new places... kept looking... maybe found something... nope... Everything fell apart as fast as I could put it together. It was positively amusing until, oh, last week. And now my friend Lydia is going back to Connecticut, because she has no job and she fell and cracked her knee in three places like an egg. All the best-laid plans went down like eggs.

At this moment I'm waiting for a call from my friend to let me know whether or not I can take up residence in her house. To alleviate my feeling of uncertainty and abandonment, I cast my story out upon the waters of the internet. There.

Don't worry, whoever is reading this. Things will work out. Good times are a-coming. I can hear joy barreling down on me like a runaway tourist bus on Clingman.

It's the cusp of the month. When I was in high school, this meant nothing. When I was in college, it meant that I would sign a check. When I was at Betsy, it meant that it was time to collect the always-too-little I'd gotten from various un-jobs and beg for the remainder from charitable souls. Now I'm just hoping I'll have someone to write a check to. I'm done with this house. Can't live here anymore. I put in my month's notice... looked for new places... kept looking... maybe found something... nope... Everything fell apart as fast as I could put it together. It was positively amusing until, oh, last week. And now my friend Lydia is going back to Connecticut, because she has no job and she fell and cracked her knee in three places like an egg. All the best-laid plans went down like eggs.

At this moment I'm waiting for a call from my friend to let me know whether or not I can take up residence in her house. To alleviate my feeling of uncertainty and abandonment, I cast my story out upon the waters of the internet. There.

Don't worry, whoever is reading this. Things will work out. Good times are a-coming. I can hear joy barreling down on me like a runaway tourist bus on Clingman.

Friday, September 18, 2009

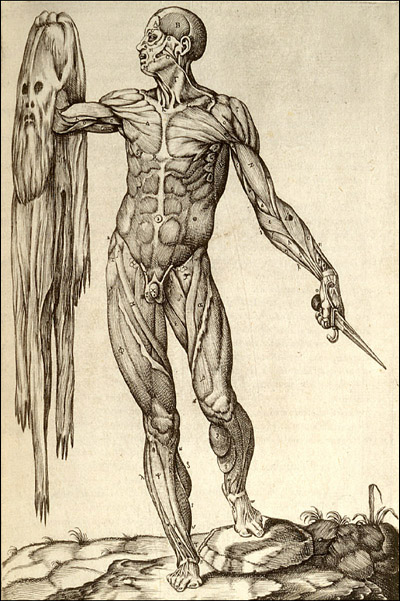

Adventures of the Body

"Misfortune comes from having a body.

Without a body, how could there be misfortune?"

- The Tao Te Ching

The Thumb

I was biking up Riverside, a long, winding road that follows the French Broad. I have passed over the railroad tracks many a time without misfortune. This time, it was raining. My front tire slipped on the steel and wedged in the crack. I flew, grouchy before I even hit the ground, but somehow I landed more or less on my feet with a mysterious combination of injuries. These things always amaze me. There was a single spot of blood on my right thumb, and the top of my right shoe was ripped open, as well as the sock underneath, as well as the skin underneath that. I pried my bike out and went on, pissed as a wet cat about the biker-unfriendliness of non-perpendicular RR tracks. Strangely, the worst part of it all is my thumb, which has developed a nail hernia. Over the past few days a bubble of meat has squished out the side of the nail, and it torments me terribly. It torments me as I type this. It tormented me for seven hours yesterday as I bashed it into things at the shop and pressed it hundreds of times onto the paper I was feeding.

The Heat

As soon as I got my paycheck, I took a chunk of it to a doctor of Chinese medicine. I have had very good luck with this kind of thing, and I want to be quite, quite well at this point in my life. The man I saw had grown up in Mexico City; his family lived in San Antonio, so we had a bit to talk about. He looked at my tongue, checked my pulse, asked me if I am frequently thirsty, etc. He said, "You are a robust person with an excess of energy that is not being moved through your body. So the energy is stagnating as heat, mostly in your liver and your uterus, but also in your lymphatic system." Which is a fairly remarkable diagnosis to make from looking at a tongue, so remarkable it sounds like palmistry, if it hadn't so exactly divined my problems. We talked for an hour about the strange constellation of physical difficulties that have settled on me like blackbirds on a telephone pole. He said the problem was complicated, but there is a root cause. There is something that derailed my health, perhaps a parasite, definitely the EB virus, and definitely compounded by a certain "excess of heat," emotionally speaking. This is why I see non-Western doctors. They are not reductionists nor materialists. They respect the body as a thing compounded of spirit and matter, and as a thing which belongs to someone, a fact which quite escapes the average practitioner.

Saturday, September 5, 2009

Gimme the Biggest Spinners You've Got. That's Right. On the Bike.

I walked into that store and went straight for the food equivalent of spinners. Due to some crimps in my unbelieving brain, I shied away from the organic bananas which cost 50 cents more a pound than the normal ones, but went straight for the rainbow trout.

I've visited this place before. There are only a few things there I can afford on my own, all of them in the legume family. But I'd window-shopped all the sweet shit. This time I was there to BUY. I only looked at the price tags to satisfy myself that this particular item really was the most expensive version they carried. I passed up all the sweets, however, due to the residue of a childhood memory. I was standing in the aisle and asking my mother for Lucky Charms, which I passionately loved, mostly to sneak under the kitchen table and pick the marshmallows out of. She said, "No, we can't get those anymore, not on WIC." The WIC (women and children's nutrition) program only allows the purchase of certain foods like meat, milk, eggs, and so on. My childish indignation was very great and accompanied by a revelation that the good things in the world are doled out by powers even bigger than my mommy. And from that time on, I inveighed fiercely against WIC, arguing that we ought to escape them so that we could buy the things we wanted to buy again. Such was the sentiment that filled this continent with my ancestors.

It was this memory that steered me away from the sweets. Because surely the powers would not allow frivolity. But everything I'd gotten was frivolous. That's why I'd gotten it! And the closer I got to the checkout, the more fearful I became. They couldn't allow me to buy this! Do not tempt Uncle Sam! I knew that the cashier, seeing my basket, would laugh at me and shoo me back to the bean aisle from whence I came.

My face got hot as I unloaded the loot. Suddenly there were two cashiers there, and a long line formed behind me instantaneously. What if I had to put all this back?

"How are you today?" (He means, "What, is this payday or something?")

"Fine."

Checking the goat cheese, "Ooh, this is so worth the price" (...of your independence and self-respect).

"Hey, Joe, can you cover me after this?" ("I don't even see the point of working anymore when little Ms. Government can come in here and buy a pint of blueberries on me.")

I handed him the card. He swiped it. It worked.

"You want a bag for all this?" ("Might as well since you're taking everything else in the store.")

I went home and made a piece of flatbread with which to eat my goat cheese, trout, and blueberries, because I considered crackers too expensive. Somehow, it wasn't that good. I didn't relish it. It had not come to me by any work I'd done, or by the work of anyone I knew. I had not had to wait until midnight, ride across town on my bicycle in a blizzard, pick a lock, and climb into a stinking cave to root it out. What had happened?

I never stole food, as a matter of principle, until after I dumpstered. Getting your livelihood from a dumpster is like sneaking behind the curtain at a theater and seeing it all from the inside out. The careful effects of makeup appear grainy and garish, the purple robes look like the thrift store polyester they are, and the new view simultaneously expands and contracts your experience. You have seen through the veneer, and the bigger story becomes apparent, that little affair going on between the director and the lead, the jealousy of an understudy. And even if you go back into the audience, you now see two shows playing one on top of the other. You are an insider because you have broken your character as audience member. You have defied the ritual and passed a barrier. Just so, the vast oceans of good food thrown away undeceived me as to the reality of the grocery store performance, and I ceased to take the contract seriously anymore. These are the options. One can go in by the front door during the open hours and pay $10 for a bag of fine blanched almonds. If one doesn't have $10, one can go to the back door after hours and take the bag of fine blanched almonds, which have been crossed off a list somewhere in red pen. Or one can go in by the front door during the open hours and take the bag of fine blanched almonds, which will be crossed off a list in red pen. This is why I allowed myself to steal, because I knew that it made no difference. The most destructive part of what I was doing did not involve food at all, it involved breaching the agreement that our society stands upon, a contract left over from a time when having food meant that you had produced something. This is not so now. The richest people are too often the ones who have done the least, who traffic in imagination. Need I even invoke the "financial crisis?"

There has been considerable discussion about whether or not welfare is really a helpful institution. According to my (yes, conservative) family, after a while it destroys initiative and self-reliance. The jury was out for me until today. Now I can say, yes, the ritual use of this piece of plastic will damage my initiative and self-reliance. But not for those reasons usually advanced; this is much more serious. This method of obtaining food is destructive because it both situates me within a world of ritual, and shows me that there is nothing to this world but ritual. The most basic human (and animal) activity of finding food is reduced to puppetry. It is more destructive even than stealing, because there is tension in stealing, there is the reality of police, security cameras, desperation; in short, it takes work. With the card, the system enervates itself and reveals its own duplicity. Nowhere do I see the necessity of work. Any rule of cause and effect is broken and I am further alienated from a world in which work produces food and inertia produces want. I drift, full of food that is tasteless, with a lump of sorrow in my throat, looking for something that has been lost, and I think I know what it is. A place where honesty and cooperation are needed and not ritualized artifacts. Rituals that expose themselves as mere ritual are putrid and frightening, and this what the "virtues" are, zombies, which the clever and even the most principled exploit.

Why work at all, at honesty or at growing food, when ritual can pass for work, and when work is an anachronism, with the sentimental sapidity of the horse-drawn plow, and hunger?

I've visited this place before. There are only a few things there I can afford on my own, all of them in the legume family. But I'd window-shopped all the sweet shit. This time I was there to BUY. I only looked at the price tags to satisfy myself that this particular item really was the most expensive version they carried. I passed up all the sweets, however, due to the residue of a childhood memory. I was standing in the aisle and asking my mother for Lucky Charms, which I passionately loved, mostly to sneak under the kitchen table and pick the marshmallows out of. She said, "No, we can't get those anymore, not on WIC." The WIC (women and children's nutrition) program only allows the purchase of certain foods like meat, milk, eggs, and so on. My childish indignation was very great and accompanied by a revelation that the good things in the world are doled out by powers even bigger than my mommy. And from that time on, I inveighed fiercely against WIC, arguing that we ought to escape them so that we could buy the things we wanted to buy again. Such was the sentiment that filled this continent with my ancestors.

It was this memory that steered me away from the sweets. Because surely the powers would not allow frivolity. But everything I'd gotten was frivolous. That's why I'd gotten it! And the closer I got to the checkout, the more fearful I became. They couldn't allow me to buy this! Do not tempt Uncle Sam! I knew that the cashier, seeing my basket, would laugh at me and shoo me back to the bean aisle from whence I came.

My face got hot as I unloaded the loot. Suddenly there were two cashiers there, and a long line formed behind me instantaneously. What if I had to put all this back?

"How are you today?" (He means, "What, is this payday or something?")

"Fine."

Checking the goat cheese, "Ooh, this is so worth the price" (...of your independence and self-respect).

"Hey, Joe, can you cover me after this?" ("I don't even see the point of working anymore when little Ms. Government can come in here and buy a pint of blueberries on me.")

I handed him the card. He swiped it. It worked.

"You want a bag for all this?" ("Might as well since you're taking everything else in the store.")

I went home and made a piece of flatbread with which to eat my goat cheese, trout, and blueberries, because I considered crackers too expensive. Somehow, it wasn't that good. I didn't relish it. It had not come to me by any work I'd done, or by the work of anyone I knew. I had not had to wait until midnight, ride across town on my bicycle in a blizzard, pick a lock, and climb into a stinking cave to root it out. What had happened?

I never stole food, as a matter of principle, until after I dumpstered. Getting your livelihood from a dumpster is like sneaking behind the curtain at a theater and seeing it all from the inside out. The careful effects of makeup appear grainy and garish, the purple robes look like the thrift store polyester they are, and the new view simultaneously expands and contracts your experience. You have seen through the veneer, and the bigger story becomes apparent, that little affair going on between the director and the lead, the jealousy of an understudy. And even if you go back into the audience, you now see two shows playing one on top of the other. You are an insider because you have broken your character as audience member. You have defied the ritual and passed a barrier. Just so, the vast oceans of good food thrown away undeceived me as to the reality of the grocery store performance, and I ceased to take the contract seriously anymore. These are the options. One can go in by the front door during the open hours and pay $10 for a bag of fine blanched almonds. If one doesn't have $10, one can go to the back door after hours and take the bag of fine blanched almonds, which have been crossed off a list somewhere in red pen. Or one can go in by the front door during the open hours and take the bag of fine blanched almonds, which will be crossed off a list in red pen. This is why I allowed myself to steal, because I knew that it made no difference. The most destructive part of what I was doing did not involve food at all, it involved breaching the agreement that our society stands upon, a contract left over from a time when having food meant that you had produced something. This is not so now. The richest people are too often the ones who have done the least, who traffic in imagination. Need I even invoke the "financial crisis?"

There has been considerable discussion about whether or not welfare is really a helpful institution. According to my (yes, conservative) family, after a while it destroys initiative and self-reliance. The jury was out for me until today. Now I can say, yes, the ritual use of this piece of plastic will damage my initiative and self-reliance. But not for those reasons usually advanced; this is much more serious. This method of obtaining food is destructive because it both situates me within a world of ritual, and shows me that there is nothing to this world but ritual. The most basic human (and animal) activity of finding food is reduced to puppetry. It is more destructive even than stealing, because there is tension in stealing, there is the reality of police, security cameras, desperation; in short, it takes work. With the card, the system enervates itself and reveals its own duplicity. Nowhere do I see the necessity of work. Any rule of cause and effect is broken and I am further alienated from a world in which work produces food and inertia produces want. I drift, full of food that is tasteless, with a lump of sorrow in my throat, looking for something that has been lost, and I think I know what it is. A place where honesty and cooperation are needed and not ritualized artifacts. Rituals that expose themselves as mere ritual are putrid and frightening, and this what the "virtues" are, zombies, which the clever and even the most principled exploit.

Why work at all, at honesty or at growing food, when ritual can pass for work, and when work is an anachronism, with the sentimental sapidity of the horse-drawn plow, and hunger?

Friday, September 4, 2009

The Floating World

I have just received my Appalachian ID -- the food stamp card. It is emblazoned in glorious, hopeful, faux-credit card fashion with our very own red, white, and blue, and, like a huge beer, it makes me feel both very relaxed and a touch off-kilter. Let me tell you, friends, my days of crashing art galleries for Flufferspam hors-d'oeuvres are over. I am dining at big brother's table tonight. When I called the help line to hear my balance read to me by the kindly machine-matron, I had to keep pressing the repeat button. Really? No, REALLY? I burst out laughing. It effectively trebles my monthly income. Now, it is crass to discuss personal financial matters in public, but bear with me. I am trying to decide how to feel about this.

I could think of it as an extended government loan. I will pay it off unless I die in February, in taxes or whatever. I am learning a skilled trade, which is far better than a liberal arts degree, so it could be a kind of scholarship. Plus the only people I know who don't have food stamps just moved here. So I'm joining a community.

Still, in some way I feel slightly robbed of reality. This is simply absurd. No single person, however poor, could eat this much in a month. Why should I be given this? Because I'm an American citizen? What the hell is that? I will, of course, be giving large amounts away. I will also be stockpiling, Depression grandma fashion, nonperishables and canning/freezing perishables in case when the term is up I'm still broke. But there's something warped about it, the way it feels warped to get infinite free plastic bags for life whenever you check out at a grocery store, or to be able to fly through the air across the world in hours for a month's salary. It doesn't add up. The labor, the benefits. Somewhere, someone is paying. Food does not come from a card. Food comes from work, and only work.

In a bout of homesickness, I started doing research on south central Texas. I found an online database of native plants, complete with descriptions of edibles. The list is long. I remember living on the Medina River (the banks of which are now known to have been peopled continuously for over ten thousand years). I remember the plants, every strange fruit in all their seasons, wild seasons that made the snowflake cutouts we did in school seem naive and picturesque. The native plants were not like our peach trees, our fat hybrid sweet corn, simpleton carrots, foreign cabbages. They were spare, strangely colored, and terrifying. Poisonous? Who knew. I picked them sometimes and mashed them into soups and pretended to eat. If one of the uncountable numbers of Medina River people could have seen, they might have laughed, or cried, or marveled at my devotion. Because I always carefully poured out and buried the stuff after, afraid of poison. They were feasts. Nearly all those unstoried fruits I feared were gifts, and I never knew. Learning this, a plan sprung fully-formed from my newly blown mind: what if one were to remake one's own body with the materials of one's land, eating only what one could dig, catch, pluck, and snare? They say it takes seven years for all the cells in the body to turn over, and then, almost alchemically, one could become a place. An urban myth, maybe. Seven is such a poetic number.

The first European in south Texas was Cabeza de Vaca, Head of a Cow, who was shipwrecked at Galveston Island with a boatload of would-be conquistadors. They crawled ashore, "naked as the day they were born," and lay down to die in an alien land. But they were found and nursed back to health by a people who subsisted entirely upon what their hands could dig, catch, snare, and throttle. Beetles, spiders, fish, lizards, roots, mussels, termite eggs, and soil. "I believe these people would have eaten rock, if their land was made of rock," said de Vaca. He also said that they were never full. They wandered the coasts and rivers up and down in search of food. He was astonished at the women, who woke several times in the night to tend the root-cooking fires (they had the misfortune of having for a staple food a kind of root, lost to posterity, that had to be cooked overnight) and rose before daybreak to hunt more food. In the late summer, all the peoples of what would later be south Texas and northeastern Mexico convened in what is now Atascosa County and southward to gorge and celebrate the prickly pear. De Vaca eventually became a trader between tribes, and then a doctor, healing by the sign of the cross and a prayer to God. Interestingly, he wandered with those people for seven years. His body, once that of Spain, with perhaps an admixture of Marco Polo's Eastern spices, became purely that of the new world.

Those, then, are the kinds of labors it should take to keep a toehold in the world. How is it that I am floating above the earth now, that I live without having to dig, to chase, to tend fires all night, to watch the seasons, even to pray? How can I do this? They say it's technology that has multiplied our powers so that I can walk into a building and get food for free all this winter, without the faintest shadow of fear of starvation, but I don't even know what that technology might be. I don't run any machine that produces food for me. I am a beneficiary of some potent sleight-of-hand.

When the Betsies and I lived out of the organic boutique dumpsters, on the fat of the fat, we sometimes prayed to the dumpster gods to be kind to us and deliver us extra large papayas. And you know what? They did. They always did. But how?

What is this unreal world that secretes papayas in the dead of a Denver winter, where food from anywhere in the world flies into my arms at the swipe of a card? What are we standing on? Or whom? When will we come down?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)